The Taiga, also known as the boreal forest, is the largest land biome on Earth, stretching across North America, Europe, and Asia in the high northern latitudes. Characterized by its dense coniferous forests, long, cold winters, and short, wet summers, it is a world teeming with a diverse array of life.

It’s crucial to understand the food web within this unique ecosystem, as it reflects the complex interactions between organisms and their environment. I’ve always been amazed how this ecological tapestry is held together by the intricate relationships between its organisms.

As we delve deeper into this fascinating ecosystem, we’ll uncover the intricacies of life in the taiga and explore how these organisms interconnect in a perpetual dance of life and survival.

What is a Food Web?

food web is a complex system of interconnected food chains in an ecosystem. It’s a visual depiction of who eats whom, showing the complex interactions between different species and the flow of energy and nutrients through the E.

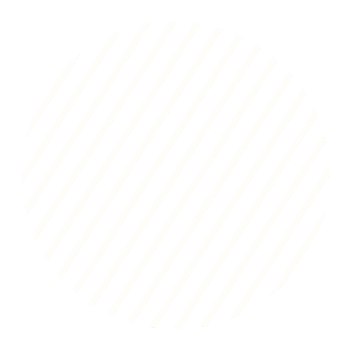

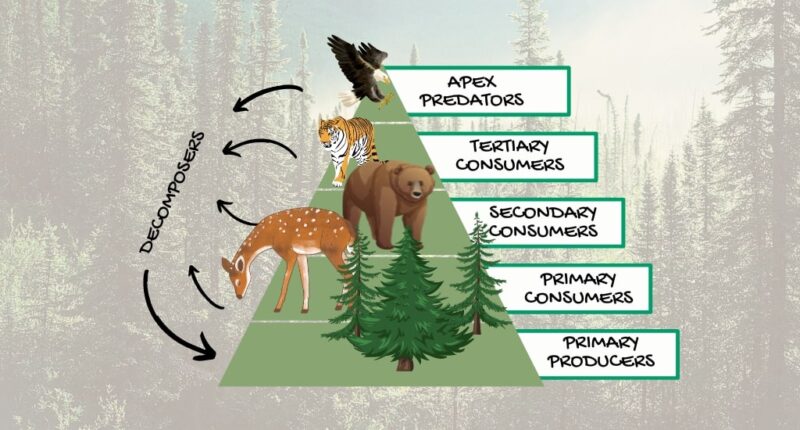

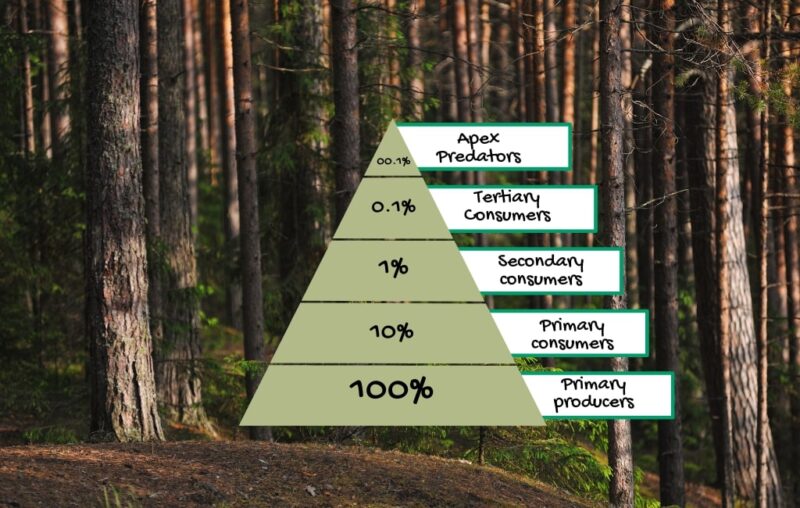

It’s not a linear progression but rather a network of connections that illustrate how all life in an ecosystem is interrelated. Organisms are grouped into various trophic levels based on their role in the flow of energy.

At the base are the primary producers, organisms that convert sunlight into usable energy through photosynthesis.

The subsequent levels consist of consumers, organisms that derive their energy by feeding on others. Consumers are categorized as primary, secondary, and tertiary based on their place in the food chain.

Understanding a food web is vital to comprehending an ecosystem’s dynamics as it reveals the connections between different species and their environment. Each organism plays a distinct role, and changes to one part of the web can have far-reaching impacts on the entire ecosystem.

Overview and Key Features

Covering a vast area across North America, Europe, and Asia, taiga biome forms a green crown spanning the northernmost reaches of the planet. It is characterized by long, harsh winters and short, moist summers, providing a unique environment for a variety of organisms.

Its most prominent feature is vast forests dominated by coniferous trees. Spruce, fir, and pine trees tower over an understory of mosses, lichens, and berry-bearing shrubs. These plant species have adapted to endure the long, freezing winters and to make the most of the short growing season.

The taiga is also home to a diverse range of wildlife, from large herbivores like moose and reindeer to predatory carnivores like wolves and bears.

Despite the harsh climate, life in the taiga thrives, weaving together in a complex food web that ties every organism to the larger ecosystem.

Producers of the Taiga: Trees and Plants

In the taiga ecosystem, the primary producers are the trees and plants that convert sunlight into energy through photosynthesis. Dominated by coniferous trees like spruce, pine, and fir, the taiga’s vegetation has adapted to its extreme environment, allowing it to survive and even thrive in the harsh conditions.

Coniferous trees are well-suited to its long winters and short summers. Their needle-like leaves minimize water loss, and their conical shape helps shed heavy snow to prevent branch damage. These adaptations allow them to photosynthesize year-round, providing a continuous energy source within the food web.

In addition to coniferous trees, it is home to a variety of other plants that contribute to the food web. Berry bushes provide food for various herbivores, while mosses and lichens offer sustenance for smaller organisms. All these plants play an essential role providing the foundation upon which the rest of the ecosystem depends.

Primary Consumers: Herbivores

Herbivores, or primary consumers, are the animals that feed on the plant life. These include large mammals such as moose and reindeer, as well as smaller creatures like snowshoe hares and voles. Each of these animals has developed unique adaptations to survive the taiga’s challenging climate and to make the most of its food resources.

Moose, the largest of all deer species, feed on the leaves and twigs of trees and shrubs. Their long legs help them navigate through deep snow, and their wide, flat teeth are perfect for grinding down fibrous plant material.

Reindeer, also known as caribou, graze on lichens, mosses, and green vegetation. They have a specialized digestive system that allows them to extract nutrients from hard-to-digest plant matter.

Snowshoe hares and voles also play an integral role in the food web. These smaller herbivores feed on a variety of vegetation, including tree bark, twigs, and grasses. In turn, they provide a vital food source for many of the carnivores.

Secondary Consumers: Carnivores and Omnivores

Carnivores and omnivores in the taiga ecosystem form the next level in the food web. These secondary consumers, which include animals like lynx, wolves, and bears, obtain their energy by preying on herbivores.

Lynx are specialized predators whose diet primarily consists of snowshoe hares. These elusive cats have sharp retractable claws and keen eyesight to help them capture their prey.

Wolves, on the other hand, are pack hunters that primarily target large herbivores like moose and reindeer. They employ cooperative hunting strategies to take down these large prey.

Omnivores like bears play a unique role in the food web. Grizzly and brown bears have a varied diet that includes berries, roots, insects, fish, and mammals.

Their dietary diversity means they have an extensive influence on several other organisms in the ecosystem, and their role can vary from a primary consumer to a tertiary consumer, depending on their diet.

Tertiary Consumers

Tertiary consumers are the top predators. They are often large, dominant carnivores that have few, if any, natural predators of their own. One of the most formidable of these in the taiga is the Siberian tiger, an apex predator that plays a vital role in maintaining the balance of the ecosystem.

Siberian tigers, also known as Amur tigers, are powerful hunters that can take down large prey like deer and wild boar. They have a broad territory and are solitary animals, often requiring vast, undisturbed forests to thrive.

While these predators sit at the top of the food web, they’re deeply connected to the ecosystem’s health. Changes to the population of their prey can impact their numbers, and their decline can disrupt the balance of the ecosystem.

As such, these animals often become a focus for conservation efforts.

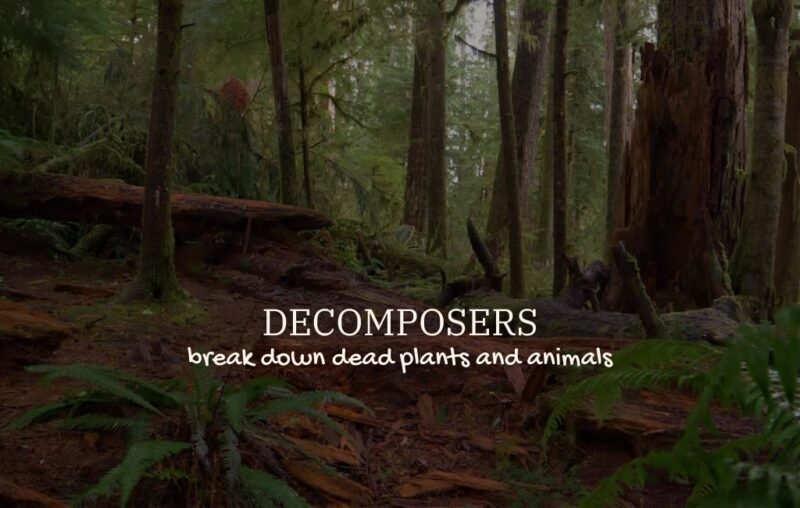

Decomposers: Nature’s Recyclers

Decomposers in the ecosystem play a critical yet often overlooked role in the food web. These organisms, which include fungi and bacteria, break down dead organic matter—such as fallen leaves, dead trees, and deceased animals—into simpler substances.

These simpler substances, or nutrients, are then returned to the soil, where they can be reused by plants. This process of decomposition is a form of recycling that allows the ecosystem to maintain its health and productivity.

Fungi are particularly well-suited to the taiga’s cold environment and are the primary decomposers of wood and leaf litter. Bacteria, too, play a vital role in breaking down dead organic matter, especially in the warmer summer months when decomposition rates increase. Together, these decomposers ensure the continuous cycling of nutrients.

Interconnections and Trophic Levels

The taiga food web showcases a complex web of interconnections between organisms at various trophic levels. These interactions reflect the transfer of energy and nutrients from one organism to another, and ultimately, back to the soil through decomposition.

For instance, when a lynx consumes a snowshoe hare, it’s not only acquiring a meal—it’s also gaining the energy that hare derived from the plants it ate. In this way, energy and nutrients move from one trophic level to the next.

However, each transfer is not 100% efficient. Much of the energy an organism consumes is lost as heat or used for its own metabolic processes. This is why there are fewer organisms at higher trophic levels—the available energy diminishes with each transfer.

Understanding these interconnections helps us appreciate the delicate balance of the taiga ecosystem. Every organism, no matter how small, plays a vital role in sustaining the food web.

Human Impacts

Human activities have significant impacts on the taiga food web. Deforestation, habitat fragmentation, pollution, and climate change all disrupt the balance of this delicate system.

Deforestation, often for timber or to make way for agriculture, reduces the habitat available for many species, directly impacting the food web. Habitat fragmentation can isolate populations, making it difficult for animals to find food, mates, or new territories. This can lead to decreased biodiversity, affecting the overall health of the ecosystem.

Climate change is another critical concern, as rising global temperatures can alter the taiga’s cold climate. This could lead to changes in plant and animal populations, disrupting the existing food web.

These threats underscore the importance of conservation efforts and sustainable practices. By protecting the taiga, we safeguard not only its many species but also the complex food web they form.

Adaptations

Organisms in the taiga have developed fascinating adaptations to survive in harsh conditions. These adaptations – whether physical, behavioral, or physiological – are crucial for each organism’s role in the food web.

For example, many animals have thick fur or feathers to insulate against the cold, while some, like snowshoe hares, change color to blend into the snowy landscape.

Many birds migrate to warmer areas during the harsh winter, while other animals hibernate or enter a state of reduced activity to conserve energy.

Plant species, too, have unique adaptations. Coniferous trees have needle-like leaves to minimize water loss and a conical shape to shed heavy snow. Their evergreen nature allows them to photosynthesize whenever conditions permit, maximizing their energy production.

Understanding these adaptations not only reveals the incredible resilience of life in the taiga but also illuminates the intricate connections within the food web.

FAQs:

How does the Taiga food web differ from other terrestrial ecosystems?

It exhibits unique adaptations, species compositions, and ecological interactions, shaped by the extreme cold temperatures and long winters characteristic of the biome.

Are there any endangered or threatened species?

Yes, some species such as the Siberian tiger and woodland caribou, are endangered or threatened due to habitat loss and poaching.

How do apex predators regulate the food web?

Apex predators play a crucial role in maintaining balance by controlling the population sizes of their prey species.

How do migratory birds impact the Taiga food web?

Migratory birds, such as warblers and waterfowl, rely on the abundant insects and berries, playing a role in nutrient transport and seed dispersal.

Are there any keystone species? If so, how do they impact the ecosystem?

Yes, the beaver is considered a keystone species in the Taiga ecosystem. Beavers create dams and ponds, shaping the landscape and providing habitats for numerous other species.

Conclusion

The taiga food web is a complex network of interactions and energy flow. From towering conifers and mighty Siberian tigers to tiny fungi and bacteria, every organism plays a vital role in maintaining this delicate balance.

It showcases the intricate interdependencies that allow life to persist in the taiga’s harsh conditions. Each creature, each plant, each microscopic organism contributes to the greater whole, testifying to the intricate balance of nature.

Preserving and understanding this fragile ecosystem is critical, not only for the survival of the species that call the taiga home but for the well-being of our planet as a whole.

Every thread in the web of life is valuable. When we recognize this, we understand that the health of our world relies on the respect and care we show towards all ecosystems, including the vast and mysterious taiga.

Related Posts:

- 10 Taiga Plants With Pictures & Facts - Boreal Forest Flora

- What Dog Food is Good for Kidney Function? 4 Nutrition Tips

- What Are the Differences Between Mammals and Birds?…

- Difference Between Male and Female Bald Eagles:…

- What Is the Difference Between a Coyote and a Wolf?…

- What Is the Difference Between Insects and Spiders?…